A high percentage of Ghanaians, which includes me, have love for President Mahama. We voted for him in the last polls, for President.

Remarkably, after calling five constituency chairmen in the Central and Western Regions to congratulate them for the hard work they put in to ensure a Mahama victory, each of them responded along very similar lines this way: “ Well, the glory belongs to GOD. What we pray for is for GOD to use Prez Mahama as a vessel to bring progress and “comfort” to ease the burden of all Ghanaians and raise the name of Ghana higher… But if President Mahama doesn’t deliver as we hope for, we will change the NDC too.”

We have come of age. Not only are such expressions of love for the country, seemingly above partisan politics, by grassroots stalwarts refreshing, but that is also what electoral politics is meant for: hope-testing for the best team. However, an even more hopeful proposition is the fact that the President himself only knows this too well. He emphasized this point in his election victory speech when he said, “The average Ghanaian has little or no tolerance for bad governance”.

And so amid the parliamentary hearing and confirmation and congratulatory messages to each of the President’s nominees, one can only hope that the appointees are cognizance of the trust imposed in them by the President and the expectations fellow citizens have of them: that it’s not about the position per se, but it’s about good performance.

But we have been here before. Since 1992, there have been a series of changes in governments and corresponding presidential appointments. Each new government came with hope and the general goodwill offered by the generality of Ghanaians; but in most cases, both the government and the performance of public officials have been lackluster. Each new administration tended to portray the outgone one as flawed, evil, and anti-state. Yet, we desire better. The hope now, more than ever before, is that President Mahama can be trusted to deliver – better than anyone else in our country can. His campaign slogan, “Building the Ghana we Want Together” is a call suggestive to every one of us that “we are all involved” and Ghana belongs to all of us. Once again, Ghana belongs to all its people. Hence, “Susubiribi”.

“Resetting” Ghana gives the subtle impression that we have veered off course for some time and need to retrace our steps to pick up from a certain past vision that worked previously, and through some fine tuning can work again. This means recalibrating the processes of statecraft to accept and implement best practices through innovation. Resetting, recalibrating, and best practices offer us not only stability of progress but also predictability. Arguably, these approaches are what will guide public servants to build and deliver the results we can appreciate. Sustainable democracy works on faith. Therefore, now must be the time to rethink or think differently (out of the box -they say) about what works best to actualize our faith in democratic governance that proposes collective desirable progress.

Progress is intentional. And so let it be known that making progress depends on changing archaic work behavior, organizational culture, and institutional poor service delivery. It is only innovation that spurs productivity and enhances value for money which translates into higher and better levels of equilibrium output. And there is a sense in which we must now look at (monitor) the innovative strategy each appointee takes to their sector institution that will deliver progressive results.

The Constitution empowers the President to “hire and fire”. The President knows his team and team members better than any of us from a spectator position. But for a good number of the ministerial appointments, one recognizes that they had either served in government before or had been minority spokespersons of the sector ministry in the previous parliament. Notwithstanding, one wonders whether it is not “the same again” and what “newness” each one is bringing to the proverbial table.

Perhaps a good instance of intentional best practice for ministerial appointment can be cited in the case of “Incredible” India. Notably, India is one of the most progressive countries today. The Indian P.M. Narendra Modi has a record of shortlisting prospective suitable candidates for a job. He will ask them to go out into the public as ordinary citizens to find out the problems or challenges of the sector and how each one would address the issue and help the P.M and India solve the problem for the people. In the case of the Union Health Minister, for example, how many quality hospitals are there now, and how many will be needed in a year? How may the minister reduce the current health-related death rate by half in, say, a year? What is the current average hospital waiting time and cure time for each type of illness reported, etc? How can India attain a better international human development index rating, by say, 5 percentage points, and so on? Same for Education, Defense, Transportation, Food and Agriculture, and other union ministries.

This approach by P.M Modi is revealing: first, by going into the public world as a pedestrian or ordinary citizen, the prospective appointee experiences first-hand encounters of what everyday ordinary citizen faces and takes notes, organizes stakeholder discussions (even if he/she may employ consultants), writes a proposal with budget and innovative sources of funding, and designs advance strategies in a logical framework how they may address the issue within precise timelines when he/she is tasked with the job of sector Union Minister. This approach informs and enables a comprehensive systemic analysis of how change and progress will be achieved. A well-thought-out approach with predictability fully informs the P.M. to mull over and decide who is better prepared and ready to deliver the results the P.M. and India need across a time dimension. And notably, P.M. Modi works with emergency timelines.

A few of my greatest disappointments with the past NPP government included the fact that it got to a point when there seemed to be no public authority to monitor and regulate anything- e.g. how much taxi operators within the Sekondi-Takoradi Metro were to charge passengers who boarded a town cabby from one place to another within the Metro. Also, there were constant arbitrary bus fares imposed by many driver-mates of minibusses that ply the Takoradi-Mankessim stretch: verbal exchanges between driver’s mates and passengers (especially elderly market women) were a common sordid occurrence. And then there were instances where upon reaching Kojokrom and seeing the traffic, the driver – although operating a station bus from Yamoransa to Takoradi- would ask passengers to deboard at Kojokrom and board a trotro to town. Pooh!

Notwithstanding, even more disappointing is the poor services of the DVLA in the Metro. The mere renewal of a driver’s license has taken almost two years and counting. Each time the license holder reports to check whether the official license is ready, it is the temporary one instead whose date would be extended to another future date. Why is the DVLA in Takoradi operating this way? Maybe, just maybe, the real bureaucratic bottleneck and red tape emanate from “Accra”. Do we understand the true individual and public cost of such inefficient operations? Perchance, are we cognizance of any of the A.U. targets (for 2063) or other international standards for human progress that are to be incorporated into our institutional approaches?

Leaving out the many public and institutional ills, one believes that resetting our country is instructive: it charges public authorities appointed by the government to ensure public care, safety, and efficiency in all forms. Institutions exist for the public good. Often, the difference between institutions in developed countries and those in low or lower-middle-income countries is that on our part, human negligence undermines institutional ethos and subsequent output. Importantly, members of the public with grievances about negative public experiences seem unsure where to go and lodge complaints. We now need a dynamic Public Integrity Section at the Office of the Attorney General and Ministry of Justice which might be similar (but extends more broadly) to what pertains in the D.O.J in the USA. Isn’t it ironic that often we have not been able to humanize, fix, or set basic minimum efficiency standards across the board for ourselves, and yet, we seem to be fixated on climate change and the possible risks of AI?

So now, it is barely five weeks into President Mahama’s four-year term. Surely some very positive moves are being made such as the alleged removal of thousands of ghost names on the national payroll. Our hopes and faith in this administration are strong. We need a better system through our government.

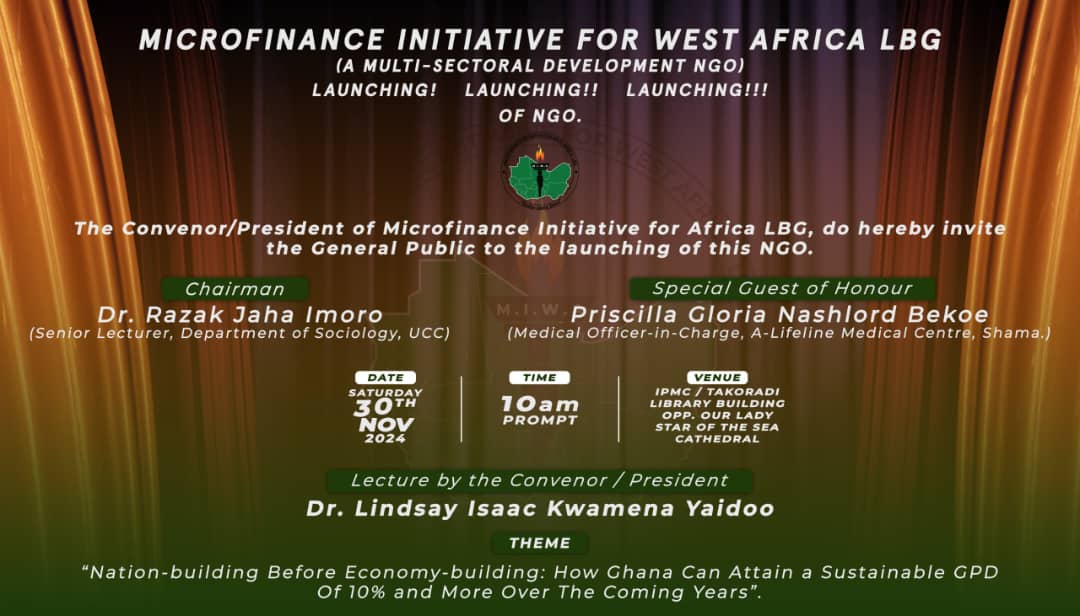

Lindsay Isaac Kwamena Yaidoo (Ph.D.) is the executive director of Microfinance Initiative for West Africa LBG (a multi-sectoral development NGO located in Sekondi-Takoradi, Ghana).

P.O. Box MC 884, Takoradi.

Email: microfinanceinitiativeforwa@gmail.com